About the Author: Jamie Thompson is a Physics teacher on sabbatical at Harding Senior High School in St. Paul, MN. The largest Title I public high school in Minnesota, Harding serves approximately 2,000 9th–12th graders, with large numbers of first- and second-generation Hmong, Karen, and Somali students.

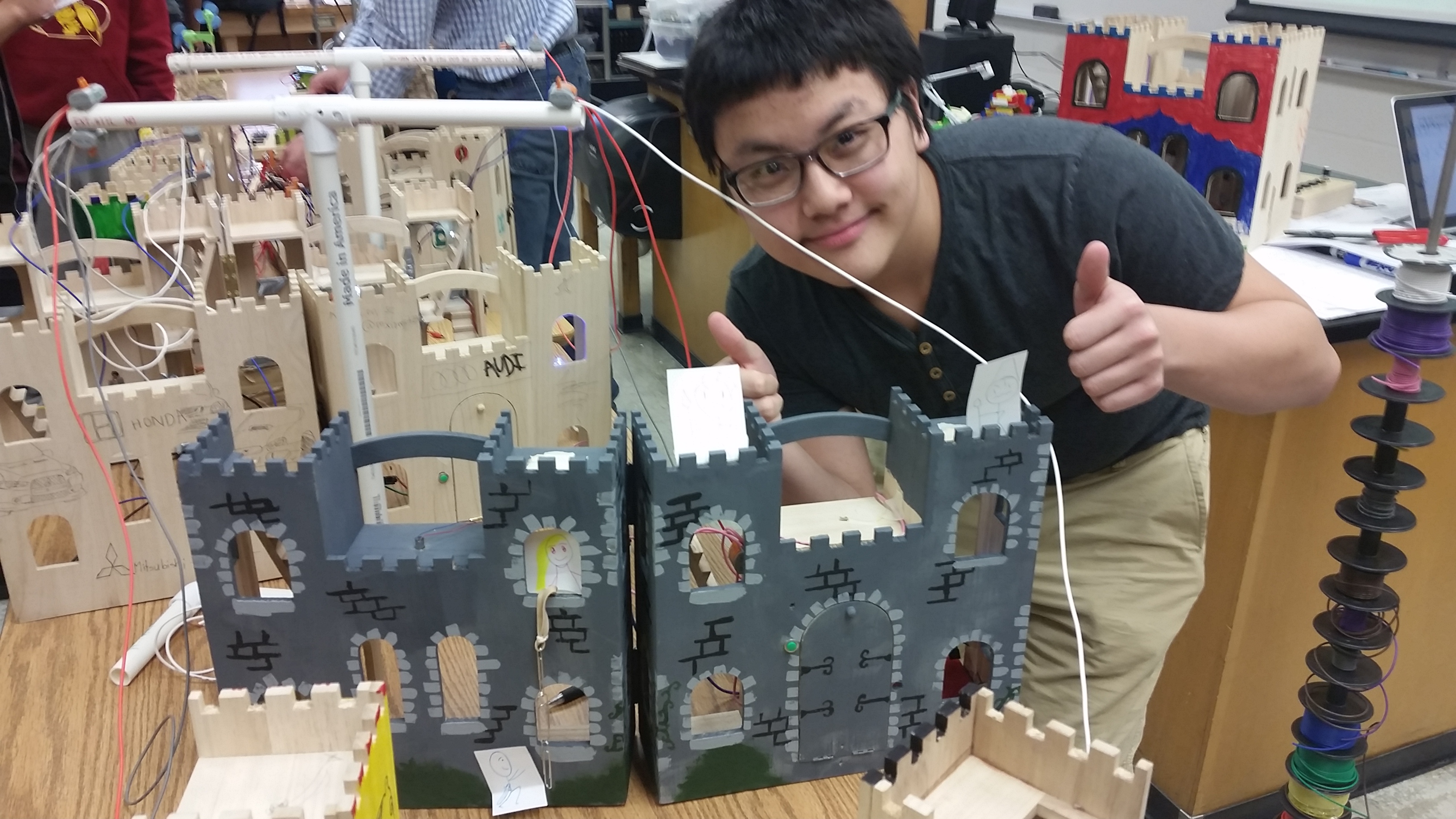

“Okay, you two. You have to leave. Your 5th hour teacher will blame me if you’re late class,” I urged Jake and Karina.

“Okay, you two. You have to leave. Your 5th hour teacher will blame me if you’re late class,” I urged Jake and Karina.

“Just one more minute. I have to glue on this last truss,” replied Karina with hot glue gun in hand and surrounded by a pile of spaghetti as her drawbridge slowly took shape.

As a physics teacher at Harding Senior High, the largest Title I high school in Minnesota, I typically stand in the hall between classes trying to get kids to class on time. I never thought I’d have to kick my students out of class or tell them they had to go home by 5 p.m., three hours after school ended. But as my colleagues in physics and engineering and I moved towards building projects with our students, this “problem” grew as well.

Wanting to take advantage of our students’ love of such projects, I applied for a sabbatical for the 2016-2017 school year. My goal was to travel the country and visit creative and innovative science programs wherever I could. It quickly became clear that the most creative and innovative programs were centered on making. So, as I traveled, I checked out dozens of maker spaces from Oakland, California, to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. I found that cities on the coasts were packed with makerspaces, while making was less well-known in the Midwest but growing steadily.

The location of these spaces, however, became a point of concern. Most maker spaces were located in private schools, charter schools, or public schools in wealthy neighborhoods. At the Stanford FabLearn conference, nearly all the schools in attendance were of the same demographic: private, charter, or wealthy.

Though we taught at a school most definitely not in that demographic, my colleagues and I were determined to bring a makerspace to Harding. If that was our goal, why not learn from the best? Thus began our journey with the Maker Ed Making Spaces program. The Making Spaces program leaders, Julia and Stephanie, are so well-versed in what is happening in the world of making and education, both in terms of maker space programs around the country and the current research around making. But the greatest advantages of being a part of the Making Space program was having a team of cheerleaders on our side and, quite simply, the deadlines.

Come September, the life of every teacher, no matter how ambitious and well intentioned, is consumed by the day-to-day demands of teaching, lesson planning, and grading. Even as a teacher on sabbatical, I had plenty of projects to consume my time. The Crowdfunding Toolkit from Making Spaces asking us to flesh out our vision for our space and future projects kept us on track. Once we started writing our online crowdfunding campaign and myriad other grants, we had lots of pre-written copy to work with. And if a last minute grant popped up, we knew what equipment we should request and were able to respond quickly.

Come September, the life of every teacher, no matter how ambitious and well intentioned, is consumed by the day-to-day demands of teaching, lesson planning, and grading. Even as a teacher on sabbatical, I had plenty of projects to consume my time. The Crowdfunding Toolkit from Making Spaces asking us to flesh out our vision for our space and future projects kept us on track. Once we started writing our online crowdfunding campaign and myriad other grants, we had lots of pre-written copy to work with. And if a last minute grant popped up, we knew what equipment we should request and were able to respond quickly.

Physical science classes are the easiest in which to incorporate making, and we already had a lot of making projects in those classes: wind turbines from whatever could be found in the recycling bins, rubber band cars from old CD’s, spaghetti bridges, and gearboxes from napkin holders. But making seemed to be the most powerful when it could be taken out of a single discipline and used to encourage students to work and create across disciplines. So as we worked on our vision for making at Harding, we pushed ourselves to think beyond science and to connect with teachers outside our department. Starting with our career and technical education colleagues was the easiest; jewelry making, clothing, and cooking lend themselves to making. We brainstormed projects such as 3D printing jewelry, adding programmable lights to prom dresses, and making custom candy molds from thermoformed plastics.

We then ventured into truly unknown territory for a group of science teachers: the liberal arts. With what projects could we possibly help our colleagues in English and history? The greatest surprise of this process was how quickly they caught the vision of making and came up with amazing projects which I can hardly wait to see come to fruition.

One inspiring example came from a pair of English teachers. Harding serves a large number of Hmong, Karen, and Somali students. Some come to Harding never having had formal schooling in their home countries or are just learning English. These two teachers will be doing a children’s book-making project with her English-language learners. Very few culturally-relevant children’s books are available for Hmong, Somali, and Karen youngsters. As our high school students make these books, they will have a reason to practice their vocabulary, create stories that are relevant to their younger brothers and sisters, and, ultimately, provide a much needed service for the youngest members of our immigrant population.

As the 2016–2017 school year draws to a close, we’re ending on a great note. Through the support of our principal and our fundraising projects, this fall we will be able to open the Innovation Studio… or the “Creativity Lab”… or the “Build-It Center.” We now have the fantastic “problem” of deciding on a name! And, we hope the other fantastic “problem” of students not wanting to leave class because they are so engaged in learning through making continues to grow at Harding.

Images provided by author.

Making Spaces is a partnership between Maker Ed, the Children’s Museum of Pittsburgh and Google.

To learn more about Making Spaces, click here.