“We learn better by doing… we learn better still if we combine our doing with talking and thinking about what we have done. But we learn best of all by the special kind of doing that consists of constructing something outside of ourselves…”

– Seymour Papert

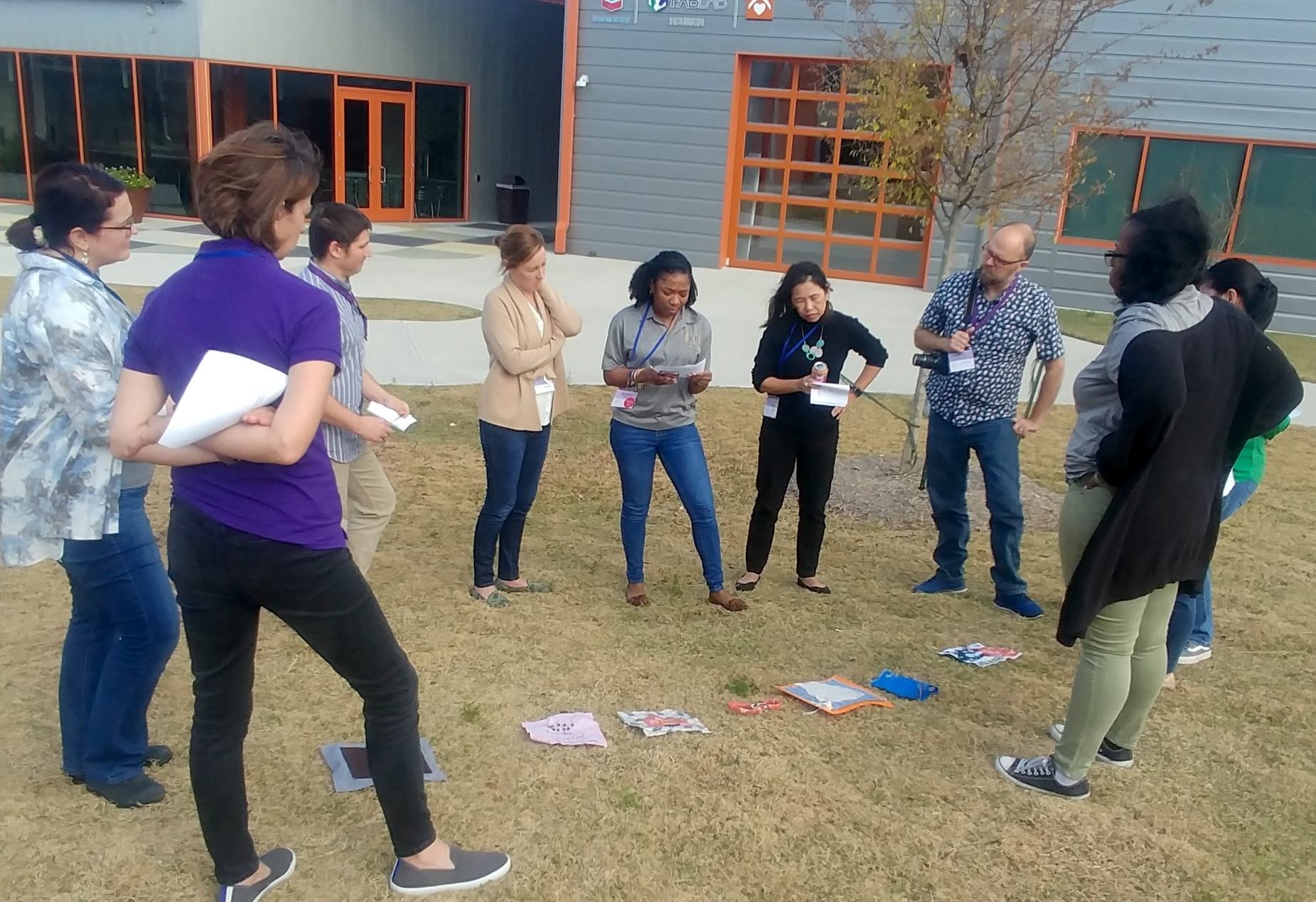

Our approach to professional development is intentionally designed to be experiential, where educators actively participate from the perspectives of their learners as a way to reflect on their own practice, facilitation, and design of maker centered learning experiences. To support educators from a variety of environments, we also integrate making experiences that represent a diversity of subject areas and media of making—making sure to develop authentic tasks in meaningful contexts. During a recent Approaches to Maker Education workshop, we combined a history lesson plan with sewing and textiles.

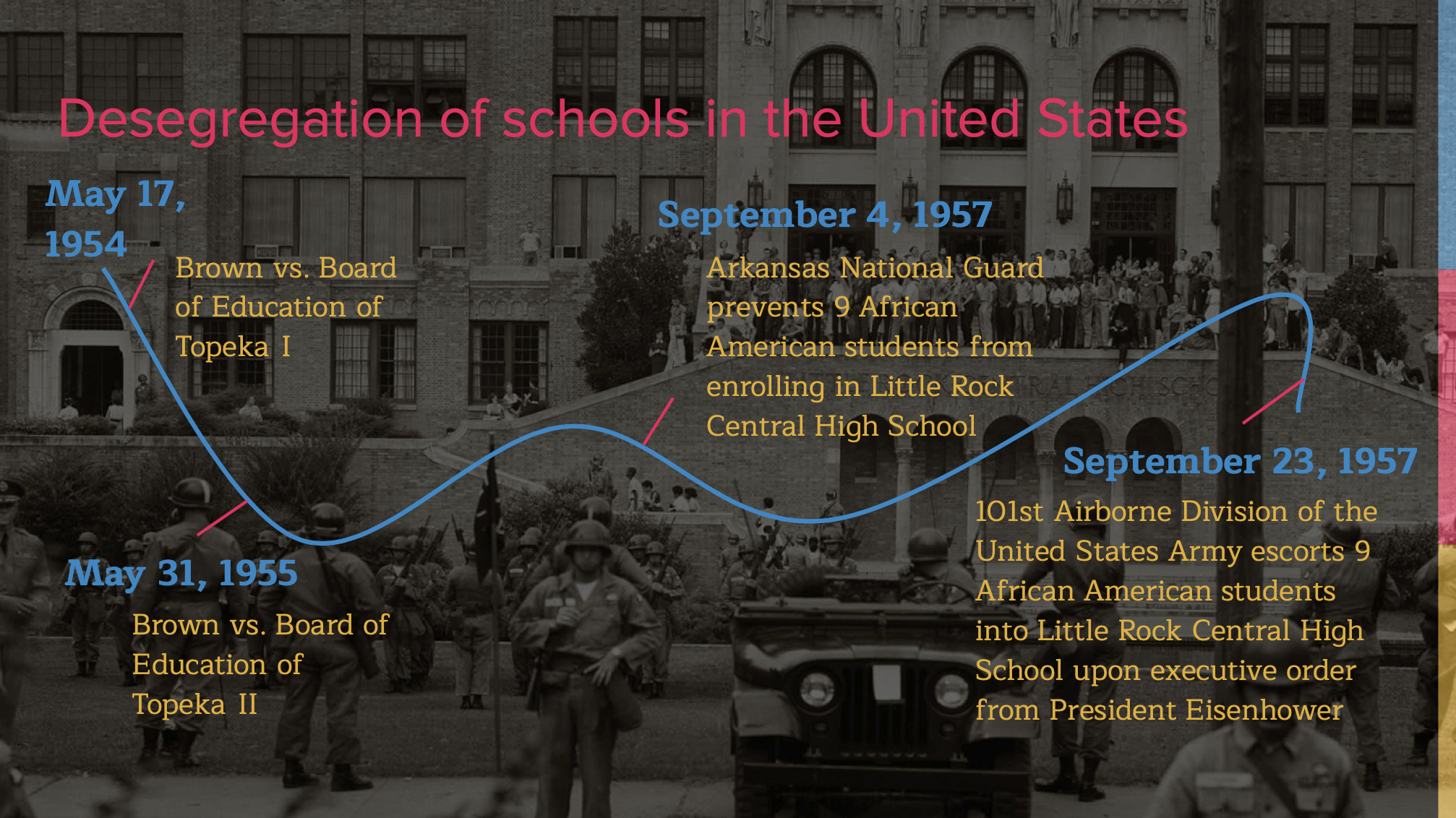

Our historical lesson plan centers around school desegregation by analyzing the Little Rock Nine crisis during the Civil Rights Movement. After the Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court ruling declared segregation in public schools unconstitutional, nine African American students enrolled in Little Rock Central High School, a previously all-white school in Arkansas. These students were subsequently prevented from entering the school by the Arkansas National Guard and had to eventually be escorted into the school by federal troops, as ordered by President Dwight D. Eisenhower.

In order to dive into the complex issues of this historical event, we first begin by giving educators a variety of primary sources that represent multiple perspectives (see the link here), such as:

- The 13th and 14th amendments from the United States constitution (1865, 1868)

- Excerpts from the Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court ruling (1954)

- Excerpts from Martin Luther King, Jr.’s article, “Nonviolence and Racial Justice” (1956)

- President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s televised address on his executive order to deploy the 101st Airborne Division of the United States Army as military protection and escort for the Little Rock Nine (1957)

- Telegram sent by the parents of the Little Rock Nine to President Eisenhower regarding his deployment of the 101st Airborne division (1957)

- Video interviews from two of the nine African American students who were enrolled in Little Rock Central High School reflecting on their experience (1985)

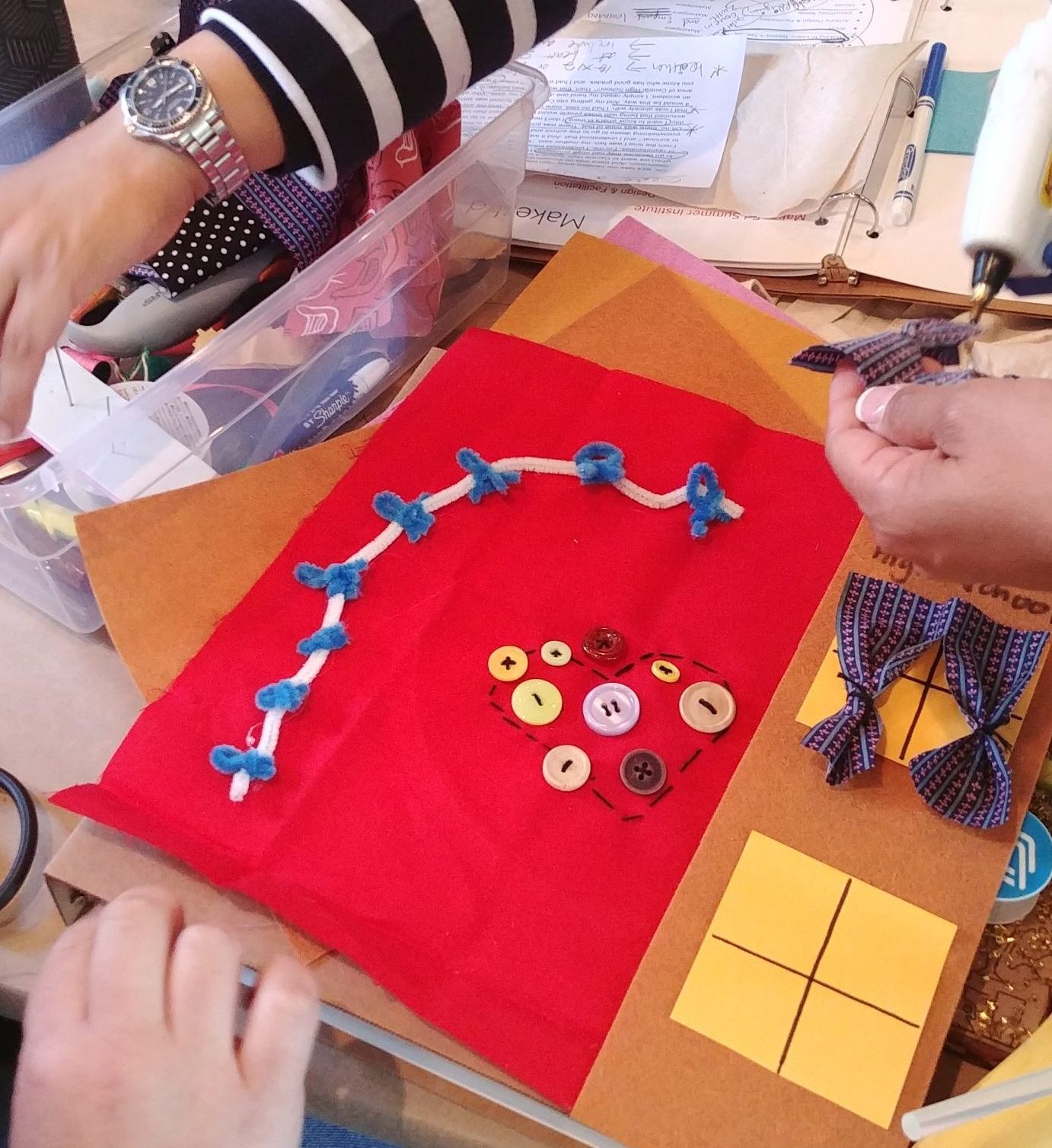

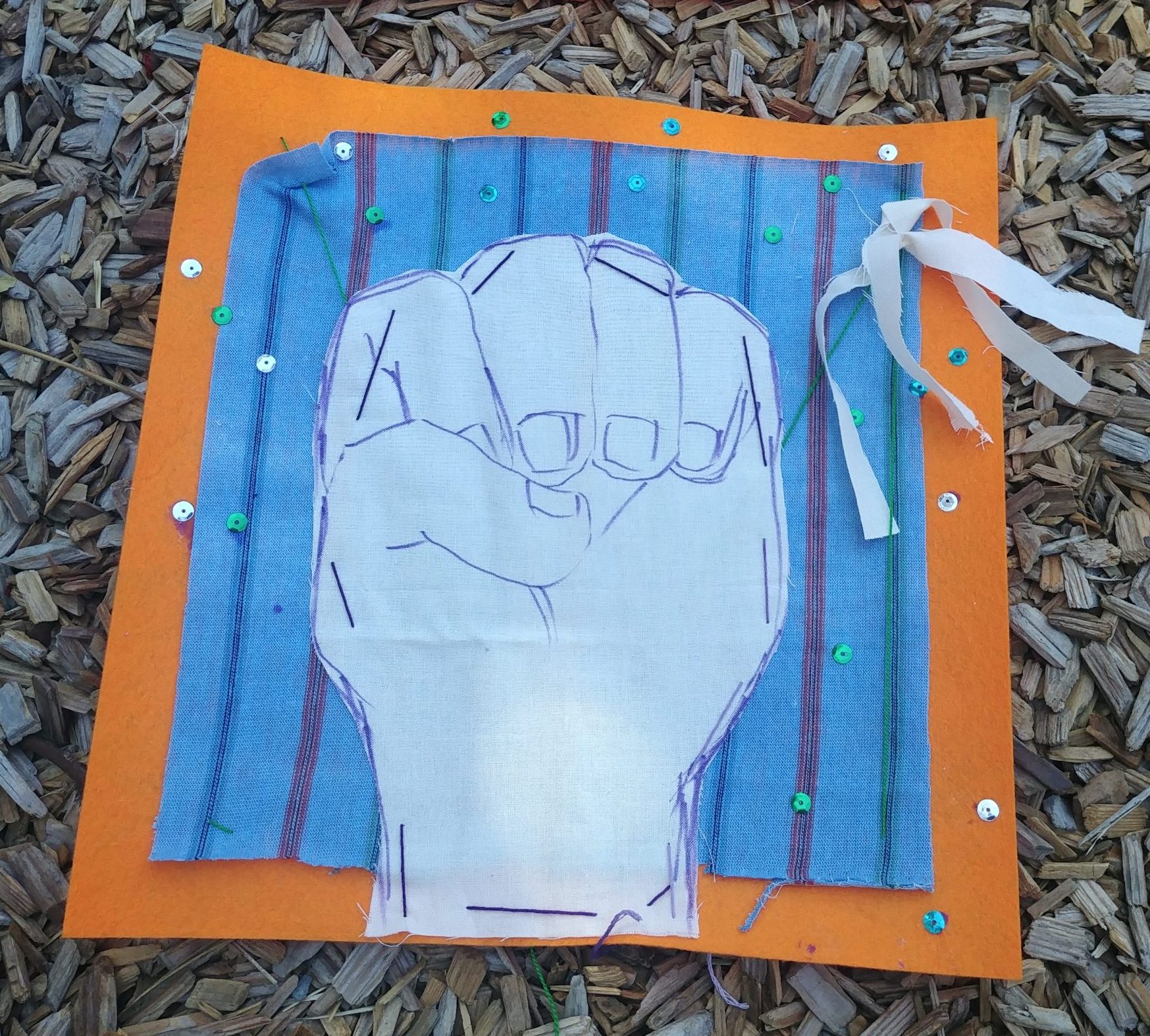

After reading and analyzing their primary source, pairs of educators create a textile representation of their analysis using fabrics, buttons, beads, thread, and different stitching techniques. This is an opportunity to intentionally choose physical objects as symbols to support their analysis of the text, translating the language in each primary source into visual metaphors.

After creating their quilt squares, participants align them in chronological order and each group reads their text and explains their visual representation. Next, we ask everyone to align their quilt square according to historical significance. It is in the physical manipulation of these quilt squares that educators are able to reflect and articulate on their analysis, debate complex issues, look closely at the voices represented, and make meaning out of their experience. Many relevant topics are brought into this discussion, such as the influence of emotional appeals from voices like MLK, Jr., where the power to enforce laws come from, the importance of voting, and the effects of racial desegregation of students. After grappling with these topics, we collectively gather questions that we are left with, such as:

- What is considered “significant” and to who?

- Whose voices are we missing from these primary sources?

- What is left uncertain from these sources?

- What parallels from these events can we find in our current timeline?

- What research can we do to learn more about the events leading up to and after these particular events?

While there is no single answer to these questions, it is through the production and discussion of these questions—which are created and driven by participants—where we meet our learning goal of developing historical thinking skills that are applicable to any social studies content: the ability to critically evaluate primary sources and to consider the significance of the words and ideas in those sources.

This lesson plan of learning about the Civil Rights Movement through sewing is just one example of our Making to Learn approach to curriculum integration. These quilt squares are used as a learning tool, not a final product. In a unit of study, learners could continue to research the answers they collected above and use them to continue their learning. They could then apply their knowledge to create a final, whole group quilt and then reflect (using both quilt squares) on how their understanding grew over time.

Ultimately, it is through the making of something physical—these quilt squares that represent an analysis of a text—where learners construct their knowledge of these historical events and deepen this knowledge as a community. Through the making, learners make their thinking explicit and have an opportunity to drive their own learning, which leads to deeper reflection. As Seymour Papert said, we strongly believe that learners learn better by doing, talking, thinking, and constructing something meaningful.