This guest post was written by Courtney Sears, a second grade teacher at Ephesus Road Elementary School in Chapel Hill, North Carolina and a North Carolina Teacher Voice Fellow with Hope Street Group. You can follow her on Twitter @CourtSears1.

Taking the Time for Making

Four year olds like to paint. For some students, seventeen years ago in my Head Start classroom, the opportunity to paint was  brand new. For weeks, they would gleefully cover page after page with a thick layer of tempera. The colors would mix into a reddish-yellowish-brown and drip down onto the easel and then to the floor. Back then, my administrators expected that an easel and paint be available to my students each day. As difficult as it was to be cleaning up paint constantly, I knew it was important for them to have time to paint that way. They were not ready to paint houses and suns and families, and asking them to do so would have been poor teaching. They were learning how the paint felt, looked, mixed, and worked. I was learning that facilitating deep understanding means giving students time.

brand new. For weeks, they would gleefully cover page after page with a thick layer of tempera. The colors would mix into a reddish-yellowish-brown and drip down onto the easel and then to the floor. Back then, my administrators expected that an easel and paint be available to my students each day. As difficult as it was to be cleaning up paint constantly, I knew it was important for them to have time to paint that way. They were not ready to paint houses and suns and families, and asking them to do so would have been poor teaching. They were learning how the paint felt, looked, mixed, and worked. I was learning that facilitating deep understanding means giving students time.

Now I’m teaching second grade, and there is no easel in my classroom. New standards have brought renewed energy and purpose to my teaching while, at the same time, there has been a sharp increase in calls for “grit” and “failure.” In my district, the growth mindset became our mantra as we designed and implemented new units around the Common Core. However, when I looked around my classroom, I saw a lot of rushing. We were rushing to fit in every standard we could before every state and local assessment we had to take. At times, my students were only rushing to finish one assignment so they could move on to the the next, never becoming as deeply engaged and invested as I knew they could be. Something didn’t feel right. Were my students developing grit or just exhausted?

Then I read Paul Thomas’s blog post, “The Poverty Trap: Slack, Not Grit, Creates Achievement.” Thomas explains that grit can be used to justify asking poor children to work harder in a system that isn’t working hard enough for them. He argues that children benefit more from slack than from grit. The greater privilege and slack you have, the lesser the consequences when you make mistakes. The more I thought about this, the more disingenuous conversations about grit and failure seemed. Was anyone really giving kids the time it takes to bounce back from mistakes and learn from them? More than the chance to fail, I wanted each of my students to be afforded the slack to be curious and engaged, try new things, and know that if they failed, the educators surrounding them would help them learn, grow, and move forward. I wanted them to have time to “paint.”

Then I read Paul Thomas’s blog post, “The Poverty Trap: Slack, Not Grit, Creates Achievement.” Thomas explains that grit can be used to justify asking poor children to work harder in a system that isn’t working hard enough for them. He argues that children benefit more from slack than from grit. The greater privilege and slack you have, the lesser the consequences when you make mistakes. The more I thought about this, the more disingenuous conversations about grit and failure seemed. Was anyone really giving kids the time it takes to bounce back from mistakes and learn from them? More than the chance to fail, I wanted each of my students to be afforded the slack to be curious and engaged, try new things, and know that if they failed, the educators surrounding them would help them learn, grow, and move forward. I wanted them to have time to “paint.”

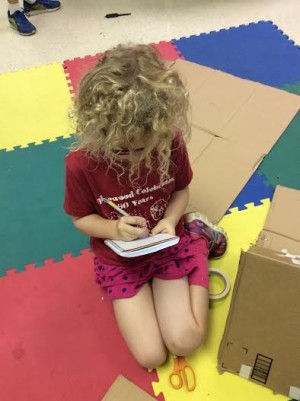

In their book, Mindset for Learning, Kristine Mraz and Christine Hertz write, “It can feel surprising when you realize that some children do not need more content, but rather more experience with how learning feels and how to work through mistakes and challenges in productive ways.” My goal became to find a way to give children more time and space to learn more deeply by setting them up with what Mraz and Hertz call “just-right challenges.” My first step was creating a makerspace in my classroom.

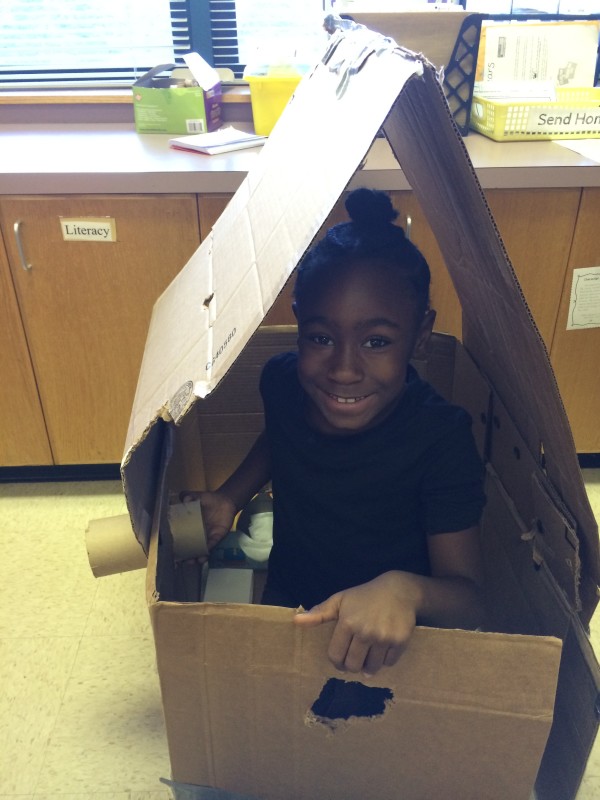

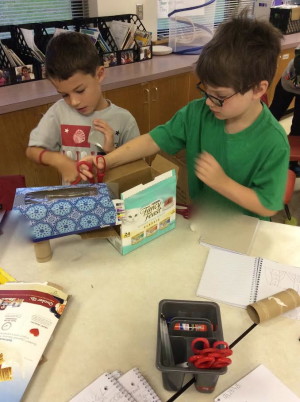

To structure use of the makerspace, our second grade team, with support from our administration, developed Maker Time, a once a week time where our students could design, plan, and build in our classroom makerspaces. We started with just a few materials–cardboard, tubes, paperboard, leds, and lots of tape. Each Maker Time begins with a mini-lesson or STEAM challenge that is followed by uninterrupted time to plan, create, and then share.

To structure use of the makerspace, our second grade team, with support from our administration, developed Maker Time, a once a week time where our students could design, plan, and build in our classroom makerspaces. We started with just a few materials–cardboard, tubes, paperboard, leds, and lots of tape. Each Maker Time begins with a mini-lesson or STEAM challenge that is followed by uninterrupted time to plan, create, and then share.

During Maker Time, my classroom is full of busy students facing and learning from just-right challenges. Two students made light-up princess crowns. They began with corrugated cardboard but realized it wasn’t flexible enough to wrap around their heads. After a brief discussion, they got paperboard and re-made the headbands, which bent to the shape of their heads, and then added hearts and LEDs. Another duo designed a shoe and wondered how to lace it. With some teacher encouragement, they unlaced a real shoe, learned how to lace it, and then used a pipe cleaner to lace their cardboard shoe. A boy, working alone, made a “tiny, sturdy, notebook” with pictures of all the holidays his family celebrates in a year. The first time he used the hole punch, the holes were too close to the edge of the paper; he realized he needed to try again, and he moved the hole punch in a quarter of an inch.

In those moments, I am confident that my students developed skills they need to be curious, engaged, and independent learners. Maker Time provides routines and structures that make risk-taking feel safe to children and prepares them to take on well-planned instructional challenges in other parts of our school day. Maker Time also shows me over and over again what just-right problem solving (and failure) look like. I take these observations to heart when I am teaching core subjects so that I can see the same joy, enthusiasm, and risk-taking in every part of our day. Seventeen years ago, I had an easel in my classroom because it gave students the real time they needed to gain a deep understanding of paint and the art of representation. The makerspace is the new easel in our classroom.