Edward P. Clapp, our guest author and a presenter at Maker Faire New York this weekend, is a principal investigator at Project Zero where he is a co-director of the Agency by Design initiative, an investigation of the promises, practices, and pedagogies of maker-centered learning. The Agency by Design Framework for maker-centered learning is outlined in the recent book, Maker Centered Learning: Empowering Young People to Shape their Worlds (Jossey-Bass, 2016).

······················································································································································

As many readers will know, educational initiatives that emphasize making, engineering, and tinkering are becoming increasingly popular in K-12 education. At the heart of many of these enterprises is an interest in incorporating the practices and ethos of the Maker Movement into education—something my colleagues and I refer to as maker-centered learning.

With all of this interest in maker-centered learning is on the rise, some are beginning to wonder, “What is really worthwhile about maker-centered learning?” While many articles in the popular press have pointed to proficiency in the STEM subjects and raising awareness and interest in the STEM professions as the primary outcomes associated with this work, others have wondered if there are even greater purposes behind the growing interest in maker-centered learning.

A long time maker myself, since 2012, I have enjoyed the privilege of working with a talented group of researchers at Project Zero—a research center at the Harvard Graduate School of Education in Cambridge, MA—to explore this very topic. My colleagues and I call our research project Agency by Design, and we have described our work as an investigation of the promises, practices, and pedagogies of maker-centered learning. Having spent many hours speaking to educators and thought leaders at the forefront of maker-centered learning, while also conducting site visits to various makerspaces and maker-centered classrooms across North America, what we have learned is that maker educators are indeed interested in supporting proficiency in the STEM subjects, but they see STEM-related learning objectives as being secondary to building character and developing a sense of agency amongst their students.

Focusing on agency as a core learning outcome is exciting! However, as researchers, we found that simply identifying agency as a learning objective can feel a bit ambiguous and abstract—and maybe even a little hard to hold onto. So instead, we established an understanding of agency as seen through the lens making. We call this concept maker empowerment. We define maker empowerment like this:

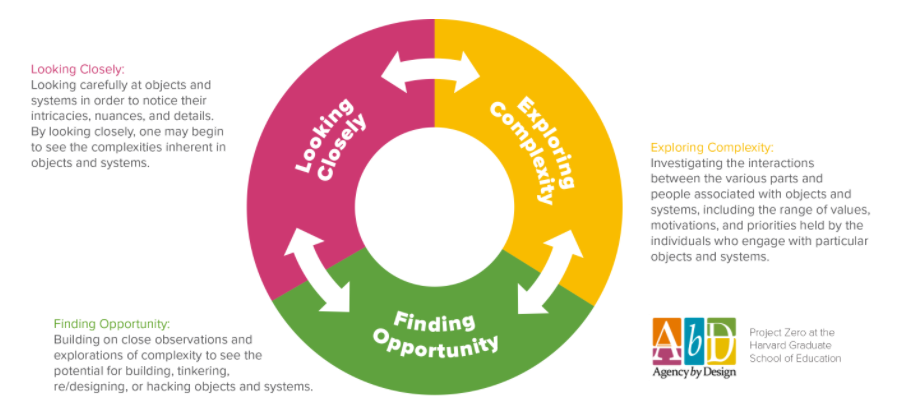

- Maker empowerment: Having a sensitivity to the design of objects and systems along with the inclination and capacity to shape one’s world through building, tinkering, re/designing, or hacking.

Of course, not everyone who teaches in the maker-centered classroom has this definition of maker empowerment posted on their walls like a credo—or a manifesto (though some do!). But we believe that, know it or not, many—if not most—maker educators strive to develop maker empowered students through their work, more than anything else.

Of course, as educational researchers interested in developing usable knowledge that can support student development across various learning environments, merely identifying maker empowerment as the primary outcome of maker-centered learning was not enough for us. And so, in order to support maker educators in their pursuit of this learning objective, my colleagues and I developed an instructional framework for maker-centered learning. At the heart of this framework is maker empowerment. This dispositional outcome of maker-centered learning is further supported by a trio of actionable maker capacities and a suite of teacher- and student-friendly thinking routines.

The three core maker capacities at the heart of the Agency by Framework for maker-centered learning. Design by Matthew Riecken.

Though we certainly value the STEM subjects (and the arts and humanities, too!), it is our hope that the focus of maker-centered learning may shift away from an interest in supporting discipline-based knowledge and skills, to more rich and last learning objectives, such as building character and developing a sense of agency amongst young people. Examples that we have seen of young people developing a sense of agency and building their character range from taking the initiative to learn to sew and repair one’s own backpack, to developing a complex web of collaboration in order to provide young people in under-served schools with access to quality reading materials. We believe that by pursuing maker empowerment as the primary learning objective of the maker-centered classroom, maker educators can do great things for the young people they serve. Paramount among them is supporting the students who leave their classrooms (wherever those classrooms may be, and whatever form they may take) in believing they can truly shape their worlds.

························································································································································

About the Author

Edward P. Clapp is a principal investigator at Project Zero where he is a co-director of the Agency by Design initiative, an investigation of the promises, practices, and pedagogies of maker-centered learning, and the Creating Communities of Innovation initiative, a research study geared towards supporting educators as inquiry-driven innovators. Follow Edward on Twitter.

Edward P. Clapp is a principal investigator at Project Zero where he is a co-director of the Agency by Design initiative, an investigation of the promises, practices, and pedagogies of maker-centered learning, and the Creating Communities of Innovation initiative, a research study geared towards supporting educators as inquiry-driven innovators. Follow Edward on Twitter.