Julie Cardenas is an early childhood educator and former Maker Corps Member. In this post, she speaks to Maker Ed program coordinator Justin about traditional ways of making, cardboard, tape, and empowering communities. If you’re interested in becoming a Maker Corps Member, applications are currently open! You can learn more here.

Justin Boner, Maker Ed: We loved getting to know you and your work as a Maker Corps Member with the Children’s Creativity Museum in San Francisco. How did you get started down your path as an early childhood educator?

Julie Cardenas: I am a Head Start baby. I went through the Head Start program. I came from a family of nine. Both my parents are immigrants—my dad is from Peru, my mom is from Mexico. They didn’t have much, but what they did teach me was the real value of education. I didn’t know I was going to be a teacher until I was graduating in my last year at UCLA. I took a post-colonial literature class and one author really resonated with me. She spoke about societal change and the nuclear family and how, when you empower the nuclear family with education, you begin to see societal change. I could have gone into middle school and high school education, but I see early education as a real chance to not only work with young children and mold the first five years of their lives but to really talk to parents. You’re having parent teacher conferences and talking about social emotional development and impulse control, so you’re spending more time getting to know the family culture.

When you’re talking about the family culture, you have a chance to take what they have and to put it into the classroom culture. It’s like home culture meets classroom culture.

When we get into elementary and middle school, the assumption is that parents don’t need that hand-holding anymore, which I think is completely false. We should always take their culture into account when we’re thinking about how we can make those meaningful connections.

What are some of the recent ways you’ve been making meaningful connections between inherited cultures and making?

Julie: I have worked in the arts for a long time and I’ve been a part of the arts community in San Jose for a long time because I’m from here. I was part of the Multicultural Arts Leadership Institute (MALI), which is a group of young emerging arts leaders and also veteran leaders that meet together and spend a year talking about arts programming and leadership. During my year with MALI, we traveled to San Diego and acted as consultants to help the city think about how to revitalize some of its neighborhoods.

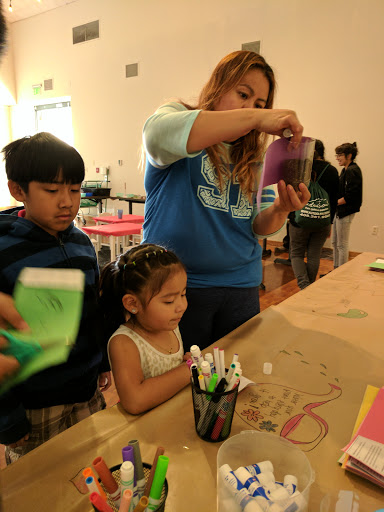

We know that Palo Alto and Mountain View and certain other parts of San Jose have this access to technology and maker education. Here on the east side, we know we’ve been making for a long time, but we don’t have a way to highlight that. I think the Mexican Heritage Plaza has been a beacon of light in the east side. They look at the arts and culture that is represented here but that has been marginalized for some years. The offerings of the nearby schools have been mostly in folklórico and Aztec dancing and some mask-making and paper maché—all really important to maintaining the sense of cultural identity. But in conversations with me, they have been asking “How do you utilize arts and technology in a responsible and intentional way to represent voice and culture?” That has been a big thing for me. So the Mexican Heritage Plaza applied for this grant to bring to other people’s attention what kind of makers we have in our community. They got the grant to cover one Mayferia event every season—Fall, Winter, Summer, and Spring—and I’ve been hired as a contractor to think about about and plan activities for families and children.

What does making at Mayferia look like?

Julie: For our first event we did paper circuits. The theme was holidays and because I’m also Mexican, a Latina, I know that holidays are important for the Mexican community. Because the holiday at that time, Las Posadas, utilizes a lot of light in the dark winter season, we decided to couple circuitry with lanterns and ornaments.

The learning opportunities for the general public were just mind-blowing. Grandparents who spoke no English were asking me in Spanish “How do I get a hold of these things? How did you learn to do this?” I had children telling me “Now I feel like a scientist!”

Something happened to them at that time. Their traditions were acknowledged but also a new thing was coupled with them. This is what I’m trying to do. I’m not trying to negate the culture there and introduce something new, like “Hey, let’s do robotics!” I’m trying to acknowledge that there is a big place for who you are. There is an opportunity to learn something new, maybe. Or, we’re just highlighting what you already have here and saying that this is important too.

In the past you’ve mentioned the impact your experience working with Google’s Childhood Development Centers has had on your teaching practice. Can you describe that influence?

Julie: Google allowed for what talent and skill I already had and then gave me more: data collection. How do you do that in a meaningful way with young children? What happens after you collect? You’ve created a thesis statement or a question about your classroom and about your children. Then you put data collection into practice. You use that data to then inform the classroom and change what current systems or materials your question first started from. It became so important and I can’t think of teaching without questions.

How do you teach with questions? And how do you know which ones to ask?

Julie: Sometimes you’re not even sure what the question is. You get a new group of children. Then you “live” with them for maybe a month and just follow their interests. The question becomes “Who are these children and what are they interested in?” You have no structure, you really don’t. You have a room set up with materials that you’re taking a guess might be of interest to the children and then you follow their day. What do they do? How do they say goodbye? What languages are represented? You follow with your team just taking running observations.

Tell me about a time when you’ve allowed the data to inform the classroom.

Julie: One day I got some new supplies. I forgot to throw away the empty cardboard boxes and left them out. The kids found the boxes. They took the boxes and then started sitting in them and then tearing them and then opening them. They stuck with it for about 20 minutes—and these are two-year-olds! Now, two-year-olds usually just parallel play, but we saw more interactions between them about how to use the boxes in different ways—some wanted to wear them and they thought that was hilarious, some wanted to build with them.

We noticed that with the building the boxes kept falling off and we wondered if the children were thinking that this was because they couldn’t keep the boxes together. So then we thought “Why don’t we offer them tape?” But for a two-year-old, having one material and then getting a new one and making the two materials live together is a really abstract thing. Maybe the children need to experience tape first beforehand, so they can know what tape does..

So we gave them tape while we were outside and they were taping themselves. They were pulling the tape as much as they could and then rolling them into big balls and then putting the balls on top of each other. We thought “They’re figuring out what tape does!” And some children got frustrated because the tape was stuck on their hands. I thought, “Yes! Tape is sticky!”

After having that experience for a week we then offered tape and cardboard boxes together to see what they would do. During our team meetings we would bring the data and observations to our table and then try to find out what some of the common things were that we saw happening in different groups. We found a lot more interaction and language happening between the two running groups. We saw a real interest build.

Last summer, while you were a Maker Corps Member, you brought your experience in early childhood education to bear on a museum setting at Children’s Creativity Museum in San Francisco. Can you tell me a little bit more about that?

Julie: I really wanted to know more about a lot of stuff and I got some really great opportunities—Maker Corps offers a lot of great seminars and online conversations. Now being away from Maker Corps for some time, I feel like I was given a gift in terms of more knowledge about tech and how to introduce technology into early learning centers. I think circuitry was my big takeaway—how to introduce circuits and different components to young children. I am more of an open-ended instructor, but introducing circuitry sometimes requires for you to be a little bit more directive, because there are different components. There’s a real difference in museum education where you have to kind of be directive because you don’t have a relationship with the visitors. Being a classroom teacher, you see them every single day.

With Lindsay [former Maker Corps Member and supervisor at CCM] at the helm, I really felt very supported and that she was just a plethora of resources. I would say something and she would go “Have you considered this?” It was really great to work with someone who really understood and had the same questions as I had. You could get into educational conversations with her—and it wasn’t superficial, but totally authentic. She was right there with me, questioning with me. That was really great. I think that Maker Corps, if it did anything truly, brought me in relationship to other educators. It brought this conversation up and it made me feel like I was still a part of something that was really important.

What have you been up to since last summer?

Julie: I think as an educator I’ve had a really interesting post-Maker Corps experience that didn’t go as planned at all. And then the current political climate in our country has informed a lot of my practice even more and certain conclusions about where I want to be have become more prevalent in where I see myself going. And then the married life—I got married in September, right after Maker Corps—it’s been fun and interesting and busy!

I’ve been subbing at De Anza College Child Development Center, where they really want me to take on a part time faculty position to support and mentor teachers. But my real passion is to really utilize the classroom as a third teacher. How does your environment inform the learning and the students that you have in your community?

Moreover, how do you use documentation to inform educators in the community who come into the classroom about the values and learning that is happening in there?

And how do children utilize documentation to inform their own self-reflection practices? That is not currently happening at the school.

I have been working on building allies with the faculty there so that when I do have another position there and I start bringing a little bit of this up, I’m not scaring people or isolating them. I’ve been sprinkling a little bit of that with some of the teachers and so far there’s been a good reception.

Do you ever feel discouraged in the face of educators and institutions who don’t want to change?

Julie: There was a little part of me that was like “I can’t really find a place for my voice in public schools. I should go back to Google.” But when Betsy DeVos became the secretary of education, I said, “No. That can’t be where we’re going.” So my commitment to public education became very important to me. Because De Anza College Child Development Center is a lab school, it is a very diverse community—children of federally funded programs and community parents. This just confirmed for me where I need to be, and even though the work is hard, it is more rewarding. We need to be empowering our communities.

Julie is currently planning the next Mayferia event—which will involve animation and a solar-paneled zoetrope! If you’re located in the Bay Area in California, check out this site for more information.