About the author: In 2016, Kate Murray stepped away from her position as lead maker educator at Space 8, an educational makerspace designed for 8- to 12-year-olds, to embark on a motorcycle journey from Alaska to Antartica. Maker Ed has been keeping up with Kate throughout her trip as she connects with maker educators and makerspaces around the world, and we are thrilled to present her story in this brand new two-part series.

In Part I, Kate explored her own maker origins and the path that led to her incredible makerspace road trip. This week, in Part II, she examines some of the lessons, challenges, and potential solutions faced by maker educators across the globe.

While traveling from Alaska to Antarctica by motorcycle, I have been fortunate to experience many maker moments across borders and perceived differences (see Part One of Kate’s post for more). These experiences led me to many stages of reflection, but beyond all else, they’ve led me to see that in growing and adapting to the input, perspectives and voices of the individuals they serve, maker educators across the world are facing similar challenges, as well as sharing in similar triumphs. Throughout my travels, three particular themes have stood out when it comes to bringing making into education.

Accessibility

Every student body is made up of a wide array of individuals’ with differing abilities, learning styles, and needs. Gender, race, and other factors of identity can greatly influence an educator’s implicit bias as well as the learner’s experience. But how do all these aspects impact who gets access to maker education? Is a makerspace possible without a great wealth of resources? (Yes!) Does it have to include tech? (No!) What approach should an educator take when they have fewer resources at hand? How can education reflect the diversity of the student body? How can it adapt to every learner? How can we teach empathy and prioritize social-emotional learning? Can paid programming or access to makerspaces coincide with greater accessibility for the community as a whole? How do we open up a sphere made up of proprietary information, software, and tools?

These are just a few of the questions that have come up again and again during my trip. Here are a few solutions that I’ve seen maker educators and their communities come up with:

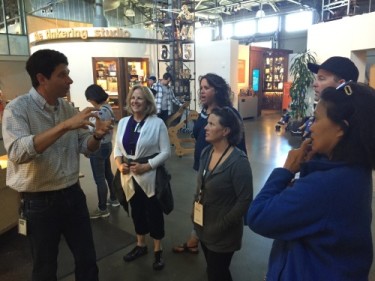

Outside the Tinkering Studio at the Exploratorium, a vending machine offers visitors significantly reduced cost kits for take-home making activities, allowing all visitors to turn their kitchen tables or living room floors into mini maker spaces. In the Creativity Lab at the Lighthouse Community Charter School in Oakland, a Maker VISTA member assists with programming that serves a diverse student population without a tech-only emphasis. In rural California, a juvenile justice center is now home to a makerspace thanks to the work of Future Development Group, and the Innovative Learning Centre of Canada has hosted maker days with East African educators in Kenya, posting their resources – such as their guidelines for Taking Making into Challenging Contexts—online for free.

In Mexico City, Hacedores balances their paid services with community outreach and access, diversifying the population served by their staff. In Medellín, Colombia, Parque Explora infuses their hands-on take to education with social management programs which give the community a voice in program design.

Accessibility takes many forms… so it is important to keep in mind that makerspaces do too. A makerspace doesn’t have to look one certain way or be contained in one building—the most important aspect is that it’s accessible to all! A rolling cart between classrooms can serve many of the same basic purposes in shifting the learning as a full fabrication lab can. In all of these spheres, participants learn empathy through design thinking, developing their self- and social- awareness and responsible decision-making skills

Maker Education is a Mindset, Not a Toolset

“Maker” is a word often associated with high-tech gadgets like 3D Printers, drones, and robotics. The “maker culture” itself is, in fact, commonly considered a technology-focused branch of the DIY movement. As such, it has grown as a method for increasing engagement in STEM fields. As an educator, however, it is important to keep in mind four points.

First, making activities don’t have to be high-tech. Low-tech crafts – such as cutting up newspapers, sewing, or take-aparts, play an equally fantastic role in shifting the energy of a learning space. All it takes is getting hands involved and questions firing. In Space 8, we used only PVC pipes, zip ties, and drills to explore the many properties of plastic through design challenges.

Second, making activities aren’t reserved for STEM.

A project called “Jitpai Jasait, Yo Soy,” showcased in Colombia’s National Museum in Bogotá, is an amazing example of the ways that making can bring history and storytelling to life. The stop-motion video, the title of which translates roughly to “Threads and sand, I am,” and was made collectively by fifth-grade students of the Wayuu tribe in Baja Buajira, Colombia. It describes life in their territory from their own perspective and details some of the significant stories of the Wayuu culture. Columbia has over 85 identified ethnicities, and it was amazing to see the ways that young people represented their culture and their version of Columbia’s historical narrative through making.

You don’t need to have all the exact right tools, latest equipment, or even a dedicated and permanent space to bring making into your own life or into education.

Whether your main materials are recycled toilet paper tubes in an abandoned closet or Arduinos in a specially designed studio, the fourth and most important point applies: making is a mindset for asking why – not just how. Activities should be inquiry-based, not step by step with expectations for the same results from every participant. It’s OK to say “I don’t know.” Making at its core is about creating and imagining potential. It is the key to solving problems with the tools available to us and innovating new solutions. While a final product can be a major plus, a making mindset embraces that the greatest benefits are found in the process, and in the experience of failure. The value of an activity should be determined by student engagement—not by the final product. I embraced this in every session of Space 8 at Thinkery, beginning each activity with an exploration of both what we feel we’re “good at,” how we can bring that into our making, and how “messing up” or discovering something we don’t know can be the very best part of the day.

Integrating Making into Your Practice

As an educator approaching making, it is normal to ask: Where do I start? What does making look like? What resources and/or space do I need? What if I lack administrative support? How do I grade and evaluate making-based activities? How can I adapt my existing lessons to involve making? Will it meet or achieve the necessary standards? How do I keep students safe while still exploring & empowering them with various tools and technologies?

From the west coast to the hills of Canada to the streets of Mexico, the greatest lesson I have learned is that for an educator to integrate making into their practice, they must first experience making for themselves. Start with asking more questions—of yourself, of your surroundings, and of all those you interact with. If you’ve got some old craft materials or tools lying around the house, pick them up again! If not, borrow some! Think of something you’d like to make for someone, a little addition you’d like to bring into your classroom or a lingering problem you’d like to fix… a piece of jewelry? a new corkboard? a leaky pipe? a hole in your favorite pair of pants? Try something out that you might have classified in your mind as “not in my realm,” “terrible at,” or “something I can pay for.” Seek out local communities around making, or around a particular craft that interests you—maybe there is a makerspace you can join, a group of educators hosting a maker educator meet up, or a woodworker you can shadow for a day. Try to experience things as a kid again—visit the science center, seek out hands-on activities, ask kids questions and try to see the places and activities from their perspective. Utilize the internet to its greatest potential for research, resources, and project ideas. But keep in mind that the best making doesn’t come from copy-and-paste methods. Always make a project your own by finding a personal connection.

Once you’ve got a taste or if you’re still looking for a place to start, know that you’re not alone! Resources, precedents, and professional development channels abound to help you integrate making into your practice. Check out Maker Ed’s Resource Library, Exploratorium’s Tinkering Fundamentals course, Future Development Group’s coaching and planning services, and numerous forums or collections. Start talking to other educators and administrators! Learn from those who have done it before. Scope out whether there might be traction for making-focused professional development—programs like the one run by the Sonoma County Office of Education, or professional development programs facilitated by Maker Ed.

As you begin your adventure in maker education, keep in mind that the ideals underlying making—collaboration, open-ended inquiry, creativity—influence the very fibers of the interactions between people of different places and spheres. What ties all makers together is a significant sense of community. We invite you to be a part of it and welcome you warmly into the fold.

Leave a Reply